Have you ever wished you could talk to someone portrayed in an old photograph? That’s exactly what I wished while researching the life of my great-great-grandmother, Annie Worthy Johnston. After delving through genealogical records and newspaper articles, and reading about pioneer life in Canada, I had an endless list of questions I wanted to ask about her experience as a pioneer.

I thought I would find information in a local history book, but to my disappointment, Annie was barely mentioned. But as one cousin pointed out, women in her generation had unequal status compared to men, often receiving little recognition for their role as pioneers. As a result, I had to use my imagination to fill in the missing details of Annie’s life. I hope I got it correct.

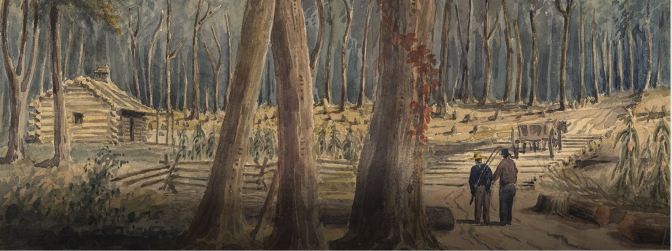

Annie’s parents, John and Janet Worthy, migrated from Britain to Upper Canada in the late 1830s, attracted by advertisements promising a new life in Canada. They settled in what is now Bruce County, an expansive and untamed area in southwestern Ontario called Queen’s Bush. My dad just called it The Bush. Their home was a cozy log cabin nestled in a towering forest close to the shores of Lake Huron. In addition to their cabin, they constructed a shelter for the livestock and cleared a portion of the forest for cultivation. The gruelling work was made even more difficult by a lengthy 50 km journey by horseback to Goderich to obtain essential supplies. Whenever my dad recounted stories of his grandparents, he emphasized the challenge of making a living in The Bush.

Philip John Bainbrigge, about 1838

Despite their hardships, John and Janet raised eight children, with Annie being their fourth. She was born in 1844 in Trafalgar, a small community just west of Toronto. Annie did not have a pampered childhood, living in a one-room cabin in the wilderness with a large family. To ensure their family’s survival, John and Janet expected all their children to help with the heavy workload and Annie learned the value of hard work at a very young age. Only after completing all her chores could she enjoy playing with the simple toys crafted by her parents or being outside with her siblings.

Winters were particularly harsh for Annie and her family. The winter of 1858 was the worst, when the settlers of Bruce County faced the threat of starvation because an unprecedented drought destroyed their crops. Thankfully, the following summer brought much-needed rain, providing great relief. Nevertheless, the settlers forever remembered that year as The Starvation Year.

Unfortunately, attending school was not an option for Annie, as it was a two-hour walk to the nearest school. Besides, with all the chores, there was no time for school. It’s likely her Presbyterian parents took on the responsibility of teaching her how to read and write, with the primary purpose of enabling her to read the Bible. With little education and few opportunities for women, I wonder if Annie ever thought of a future beyond getting married and raising her own family.

At the time of Annie’s birth, her future husband, twelve-year-old Alexander Johnston, had just immigrated to Canada from Ireland with his parents. Fortunately, their timely arrival spared them from the devastating Irish Potato Famine, which claimed the lives of a million Irish people because of starvation. However, once they arrived in Canada, they still had to contend with previous immigrants who had already settled in Upper Canada and taken up the prime agricultural land. As a result, Alexander’s family settled directly on the shores of Lake Huron, where the soil was thin and unsuitable for intensive farming. Later, when William’s sons were older, they sold and purchased land further inland and homesteaded together where the farming conditions were better.

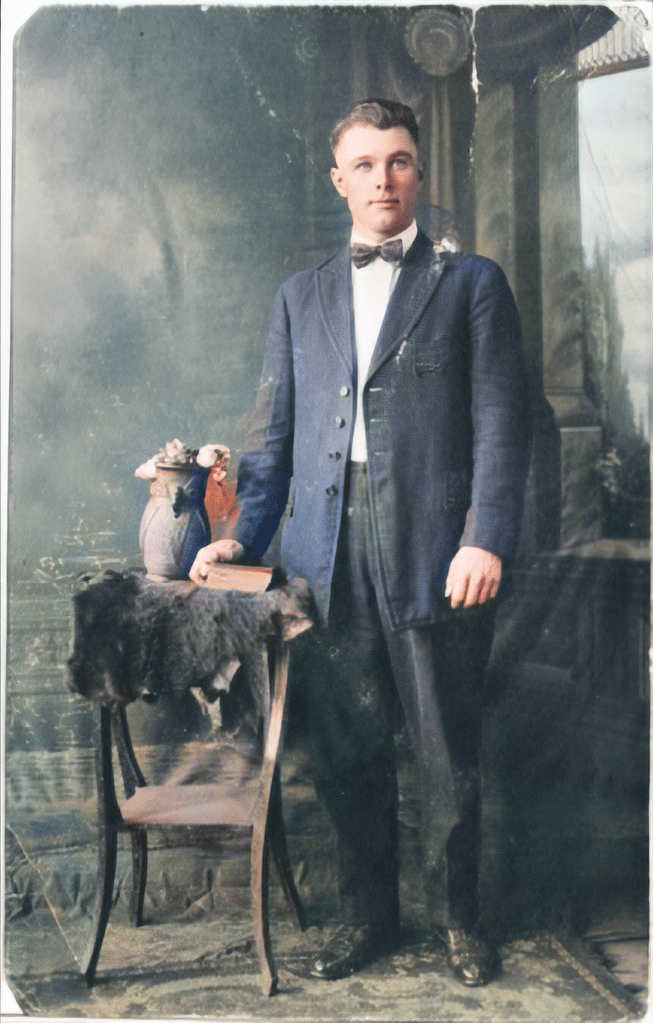

It is here that Annie and Alexander were bound to meet, given their close proximity. Annie probably had single men from miles around courting her, since eligible women were in short supply during times of high immigration. Perhaps it was Alexander’s Irish charm that attracted Annie to Alexander, but it’s likely her parents and economic considerations were the determining factor. After all, Alexander had his own homestead and the means to support a family. Consequently, on March 28, 1860, on Annie’s seventeenth birthday, she married 28-year-old Alexander, exchanging vows in the presence of friends and relatives at her parents’ house. Following the ceremony, everyone enjoyed a meal, and a dance filled with waltzes, jigs, and reels, all accompanied by fiddle music. The wedding served not only as a joyous celebration but also as a social gathering, lasting well into the early hours of the morning.

After their vows, Annie began a new chapter in her life with Alexander. In her generation, a good woman was considered as someone who strives to ease her husband’s burdens. From early morning until late at night, she did all the household and farmyard chores, while Alexander earned a living. One wife said, “We are not much better than slaves. It is a weary, monotonous round of cooking and washing and mending and, as a result, the insane asylum is a third filled with wives of farmers.”

Despite her many responsibilities, Annie had the added task of raising their children. Among her ten children was my great-grandfather, John Wesley, who was born in Goderich. Sadly, Annie’s seventh child, Mary, died when she was five years old, most likely due to one of the many childhood diseases that claimed many children’s lives during the 1800s.

Besides raising their own children, Annie and Alexander adopted their grandson Royal after her daughter Agnes had a child out of wedlock. Although it wasn’t an ideal situation, adopting Roy was a pragmatic solution to ensure his welfare and to have him feel like a valued family member.

Along with all the chores and raising the children, Annie also had to manage the farm during the winter months while Alexander went to Michigan to earn extra money by logging. One winter, after a poor wheat harvest, she had only one sack of grain to feed a growing family. Eventually, Alexander found himself in a situation where he had to sell the farm. This occurred when Alexander hired his neighbour and his team of oxen to aid him in fulfilling a logging contract in Michigan. Unfortunately, a dispute arose regarding the number of logs each of them felled because there were no stamps to prove who felled or moved them. This forced Alexander to make the difficult decision to sell the farm to settle the debt to their neighbour.

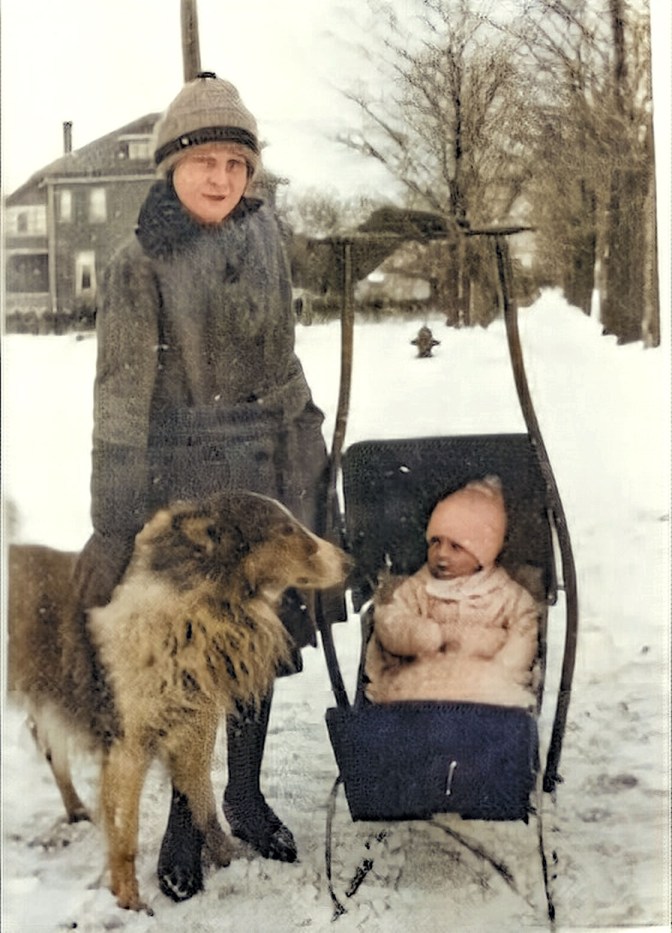

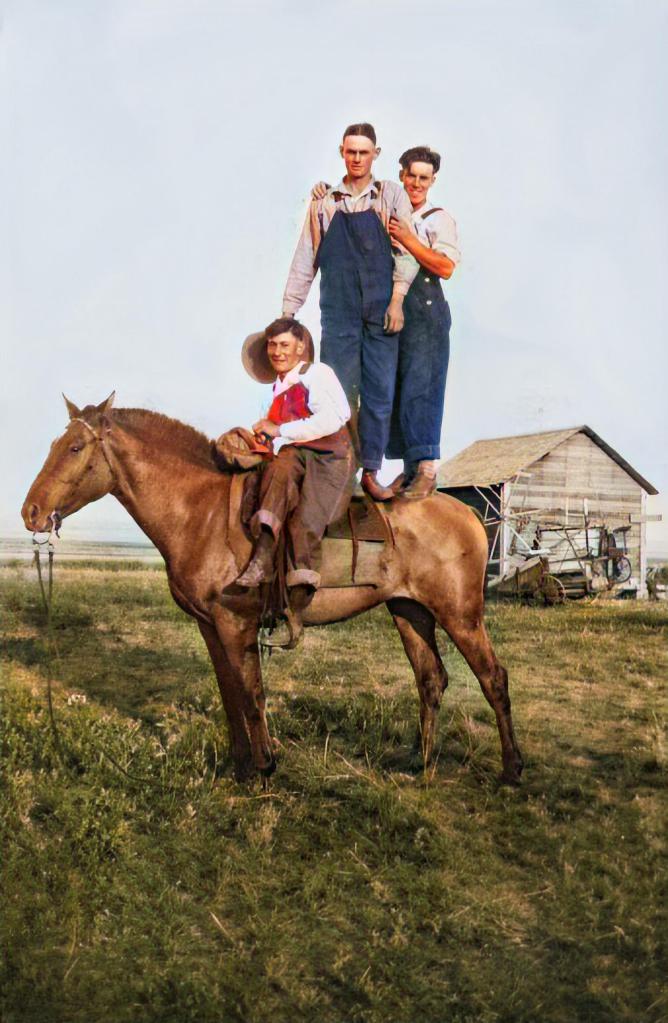

Watching their parents eke out a living and having to sell their farm, it comes as no surprise that several of Annie’s adult children settled in Western Canada during the early 1900s. The allure of abundant free land with thick, rich soil was too great to resist. Little did Annie realize that she would also find herself on the prairie, embarking on another new chapter in her life. This occurred shortly after the untimely death of Alexander when she made the bold decision to join her youngest son, James Frederick Johnston, on his homestead in Hershel, Saskatchewan. James, who was single, was struggling with an enormous workload, finding it difficult to manage on his own. As a result, at the age of 65, Annie packed her bags and embarked on a train journey to Rosetown, Saskatchewan, accompanied by Roy and her youngest daughter, Edna. As they rode the train, it must have been an amazing experience for Annie and her children to witness the vast Canadian prairie. This was especially true after being surrounded by Ontario’s forests and lakes.

Once Annie arrived, it didn’t take long before John Wesley quit his job as a teamster in Michigan and moved his family west to establish his own homestead. His family included my grandfather, John Wesley Junior, who was barely ten. However, when J.W. arrived, he couldn’t find land near Fred’s homestead. As a result, they changed plans, and Annie, Fred, and J.W. Sr. all filed for land south of Cereal. It then didn’t take long before Annie’s last son, Will, joined them homesteading south of Cereal. Eventually, Annie’s daughter Bessie showed up. Annie must have been thrilled: almost her whole family had moved west to Alberta!

I wish I could ask Annie how she felt about being a landowner. It was a unique opportunity for women living on the prairie provinces, thanks to women like Nellie McClung who fought for women’s rights at the turn of the century. I’m certain she experienced both disbelief and excitement. Regardless, with the help of her family, Annie was well-prepared to overcome the challenges of establishing her own homestead.

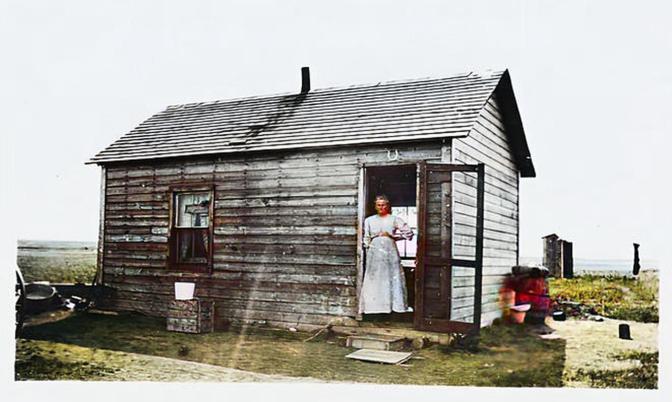

Annie had three years to meet the conditions of her claim, which involved constructing a house and cultivating a portion of her 160 acres. Remarkably, she not only met but surpassed these requirements, building a corral for livestock, a granary for storing seed, and even a shop. While most people today envision retiring at 65, clearly Annie had other ideas.

I enjoy looking at the photograph of Annie standing in front of her house. She looks confident, standing tall with one hand on her hip. I feel you wouldn’t want to mess with her and am willing to bet she had a loaded rifle mounted inside her shack to shoot any unwanted critter sniffing around the premises. I also love the horseshoe nailed above the door for good luck.

Despite her lucky horseshoe, tragedy soon followed Annie, leaving her heartbroken and shattered. First, both Edna and her baby died during childbirth, and then her granddaughter Alexia died from a fatal gunshot wound. This tragic incident occurred when her Uncle Fred fired gunshots at J.W.’s house over a dispute over a load of wheat. My grandfather, John Wesley Junior and his sisters, Ella and Alexia, were in the house, sitting at the kitchen table, when Fred fired the shots. My grandfather escaped being hit by a bullet, and Ella’s gunshot wound was not fatal. At first, it seemed that Alexia would survive, but sadly, she later succumbed to her injury in a Calgary hospital. She was only eighteen years old. Eventually, Fred was found guilty of murder and given a life sentence. Whenever Dad told the story, I could feel the sorrow his family felt because of the incident.

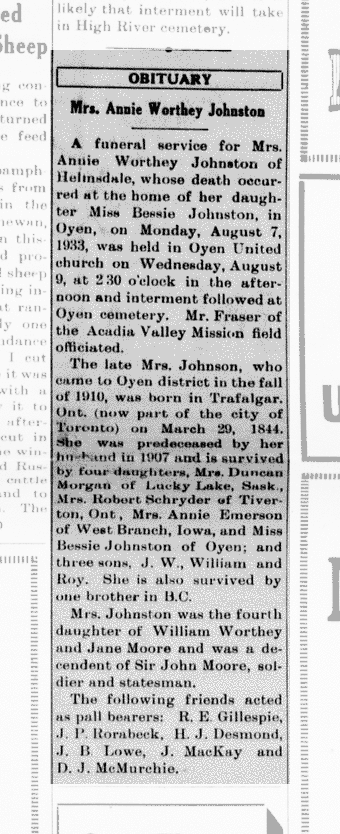

After a lengthy time searching through digital files of faded newspaper articles, I finally found Annie’s obituary in the Oyen newspaper. It surprised me to learn Annie passed away in Oyen at her daughter Bessie’s house. I expected her to stay with Roy, who took over the farm, until the bitter end, still helping with the chores.

Did I get all the details about Annie’s life correct? I doubt it, but it doesn’t matter. I can still feel proud about the fact she was among the many pioneer women who contributed to the settlement of Canada. Still, I would have loved to hear her talk about her experience as a pioneer. It’s too bad old photographs can’t talk.

Nice histography Dean. I’ve been researching my grandfather who homesteaded up in Grande Prairie area. He was adjacent to native camps and heard the drumming at nights.

LikeLiked by 1 person