I first heard about King as a child at my grandparents’ farm, where his massive horns hung at the head of the family dinner table. King was one of four oxen that brought my great grandparents’ family to their homestead on the Canadian Prairies. My dad, who was very proud of his heritage, often repeated the story to me and my younger sister and brother. When Dad told King’s story, there was reverence in his voice–King wasn’t just a barnyard animal, he was an important part of the family history.

My great-grandfather, John Wesley Johnston (known as J.W.), purchased King and the other oxen in Rosetown, Saskatchewan, in 1910. He and my great grandmother Margaret, along with their seven children, had arrived by train from Calumet, Michigan to begin their new lives as settlers on the Canadian Prairies. The children ranged in age from three to fourteen and included my nine-year-old grandfather, also named John Wesley. They were among many other pioneers arriving that spring from Canada, the United States, and Europe. My great-grandparents filed for land south of Cereal and needed to have the homestead ready for their family before winter. King, along with the other oxen, Jerry, Tom, and Bill made it possible.

My great-grandparents were excited to start a new life farming on the Prairies. They were originally from Ontario and had moved to Calumet, Michigan after their first attempt at farming failed. They never gave up their dream of owning their own farm and seized the opportunity to homestead in Western Canada after being enticed by J. W.’s mother and younger brother, who had claimed land five years earlier near Rosetown. After selling their house they left Calumet in a colonist railroad car with their settler’s effects and arrived in Rosetown a week later. From there J.W. set out for his new homestead with his younger brother Fred and the oxen team so that they could prepare it for his family.

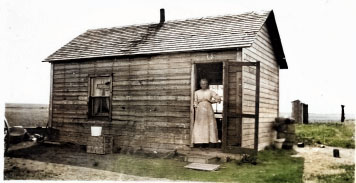

The two-hundred-kilometer trip took several days over the open prairie and it’s easy to understand why J. W. was so proud of the oxen team, especially King, who wasn’t the strongest, but was the hardest worker. The team transported a load of cedar lumber, a plow, a tent, and a kerosene stove, along with food and other necessities for preparing the homestead. Once J. W. had dug a cellar and constructed a one-and-one-half-story house, the team then helped bust up thirty acres of sod for planting grain in the spring. They also made several days-long trips to haul three and one-quarter tons of coal for fuel during the winter.

With the oxen’s help, J. W. completed most of the work by October, and then met his family in Alsask, the furthest west settlers could travel by train. King, Bill, Tom, and Jerry were not done their work: my great-grandparents had their settler effects unloaded beside the railroad track to be taken to the homestead. The team needed to make several trips taking the supplies, including five barrels of dried fruit, plenty of blankets, clothing, and the vegetables Margaret had grown that summer for the homestead. In the meantime, Margaret and the children stayed in the tent city along with other settlers. Two weeks later, the homestead was ready for the most important trip: taking the Johnston family to their new home in Alberta.

For a bunch of city kids from Calumet, Michigan, it was an adventure traveling by oxen across the prairie grassland. It was an eighty-kilometer trek, lasting over two days, and everyone walked alongside the oxen to keep the load light. They laughed, played games, and chased gophers during the journey. Although the bison had disappeared, they saw evidence that great herds once roamed the prairie. In the evening, they pitched their canvas tent and camped under the starry sky, listening to the sounds of chirping insects and coyotes barking in the distant hills, while the oxen team rested.

Once they arrived at the homestead, the oxen had a break, and before winter arrived, J. W. returned the team to Rosetown, since the homestead didn’t have a shelter for livestock yet. He arrived home in time for a special Christmas celebration with all the trimmings. I’m sure the Johnston family enjoyed listening to J. W. play his fiddle like he often did during the long, cold winter that followed.

But the story about King doesn’t end here. In the spring, J. W. brought the oxen team back and kept them until 1914, when he sold them to a neighbor. Many years later, when my grandfather ranched near the original homestead, he immediately recognized King’s horns hanging from a corral fence at a neighbor’s farm. He brought the horns home and had them mounted on a plaque with his brand. Later, he passed them down to my dad, who passed them down to me, and now they belong to my eldest son, Brett. And as you can see, my granddaughter Eleanor has staked her claim to be the next keeper of the horns, and the one to pass down King’s story.